PERIO FOR THOUGHT - July 01, 2020

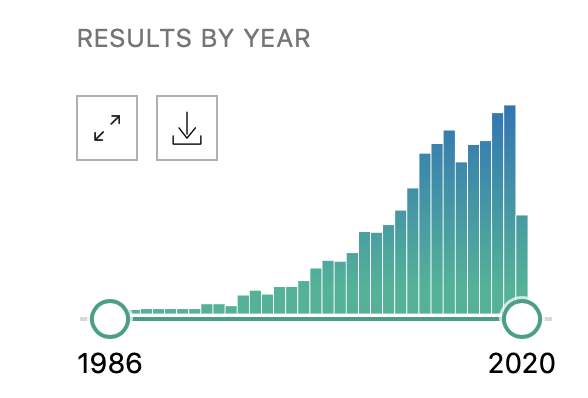

The increased presence and use of the term “minimally invasive dentistry” in the last few years has not gone unnoticed, I believe, among any of us. Pubmed shows this very clearly: there has been a logarithmic growth that highlights nearly 200 manuscripts per year in the previous 5. Like countless times already in dentistry, our beloved Periodontology has been at the forefront of these changes.

In the past few years, the minimal invasiveness has become integral to my clinical practice to the point that some of the concepts are applied as a non-disputable routine, i.e. the use of minimally invasive flaps. In fact, I always design a surgery as “minimally invasive”, and may swap to conventional flaps only after a cost-benefit analysis.

Which are the benefits of minimally invasive periodontal surgery?

The benefits are undoubtedly seen in terms of clinical efficacy and patient’s morbidity. Unsurprisingly, the reduced surgical extent has been significantly associated with an inferior level of post-surgical morbidity. What I believe was surprising at first is the superiority of the flaps in terms of clinical healing, as one might’ve expected something more or less identical to the conventional. The performance of minimally invasive flaps appears to be associated with the highest level of clinical attachment gain after surgical debridement of an intrabony defect, as our group reported (Graziani et al., 2012), on average around 4mm 1 year after surgery.

Furthermore, as already highlighted from the 2 research groups that launched minimally invasive periodontal flaps, Cortellini & Tonetti with the modified-minimally invasive technique (Cortellini & Tonetti, 2009) and Trombelli et al. with the single flap approach (Trombelli, Farina, & Franceschetti, 2007), the efficacy of the flaps is significant to the extent to which the added value of regenerative material comes into question. Reasons are mainly biological – as everything in surgery, if I may add. The use of papilla preservation flaps is associated with higher blood flow in the interdental area, which may most probably be related to a higher level of primary closure (Retzepi, Tonetti, & Donos, 2007). Consequently, this wound protection may allow for blood clot maturation, especially during the first, critical, phases of wound healing.

Working with the highest respect for the papilla also produces benefit in other types of defects, such as the very challenging horizontal suprabony defects (Graziani et al., 2014).

But in all fairness, what are the principles of MIS?

Many aspects unite all the various MIS principles:

- Reduced tissue removal/Flap extent. One of the critical aspects of minimally invasive dentistry is to “remove less”. Whether this is related to a veneer preparation or root instrumentation, the motto “the less, the better” is its fil rouge. Thus, in recent years all the efforts were put in ensuring the same efficacy, whilst with reduced manipulation. MIS also relies on the reduced access to the area. Whether this is based on a reduced flap elevation in terms of the extent of the exposure of the surgical area or on leaving one side of the surgical area intact, i.e. elevation of the flap on just one side – buccal or lingual, MIS definitely limits the surgical invasion.

- Leaving the papilla alone! (in Perio) Minimal invasiveness in periodontology is basically converging to an important surgical aspect which is: touch thou not the papilla. In fact, all the surgical interventions aim at procedural manipulation underneath the papillary structure. This is based, solidly, on the fact that in an intrabony defect, one of the two sides of the papilla might still show some healthy connective tissue attachment and therefore provide a scaffold for the healing which should reduce eventual post-surgical contraction.

- Biologically sound. The principle behind a surgical concept should translate itself in a more biologically friendly healing. In MIS this is thought to be achieved mainly through a higher blood clot stability (something I like to call a chimeric goal in periodontal surgery, due to the presence of a slippery root surface in the middle of the wound).

- Magnification. The sole use of one’s own eyes does not allow for being an excellent periodontist. This has become a mantra of modern periodontology (and all dentistry, really). Minimally invasive periodontology greatly benefits from the use of magnification. Minimal access forces the clinician to take advantage of higher magnification to compensate for a supposed inferior visual control of the surgical area in question.

- Dedicated instruments We, dentists, talk a lot about instruments, and we do it with great pleasure. In all honesty, sometimes I get a feeling that the instruments take centre stage, rather than the object(ive) of the treatment. This comes to no surprise as we are pragmatical people, we fix and adjust things: thus, instruments are crucial. MIS relies on mini-micro-ness of the instruments used to manipulate hidden areas in between minimally elevated flaps, gently and with great care.

Do we need MIS?

The answer, while not difficult, is not entirely apparent. In general, yes, I believe so. Medicine and surgery have gone through tremendous and important changes in the last century. Many of the changes in the surgical procedures have gone from being invasive and broad to higher levels of details and precision. What this also suggests is that most of what we’d performed in the past with great confidence and certainty, may now be considered overtreatment.

What is the future of minimally invasive?

The complexity I found is to clearly define where is the fulcrum balance: how much further can we push this reduction of invasiveness? What is the point after which the risk of performing an ineffective treatment becomes important? Obviously, only well-designed clinical research will provide answers to that. Keeping this in mind, we need to be ready to accept failure and swift change of opinions.

Another crucial aspect is that you can minimise invasiveness, yet you cannot minimise performance difficulty. While at first glance, it may look easy, it may become ridiculously inefficient if one has not tried the conventional approaches. I see the concept of minimal invasiveness as, once again, a journey towards wisdom. Something that happens and unfolds the more you work, and, of course, make mistakes.

Most importantly, I would urge everyone to escape from the “coolness” and the “fashionability“. It might be the case that not everything can become minimally invasive. In fact, minimal invasiveness is an oxymoron - i.e. a figure of speech by which a locution produces an incongruous, seemingly self-contradictory effect. As we like to be minimal, we still need to be invasive. Actually, the only way to be minimal is not to be invasive at all. True minimally invasive Perio will arise the day that we find the magic pill to control the disease.

Literature and suggested reads:

Cortellini, P., & Tonetti, M. S. (2009). Improved wound stability with a modified minimally invasive surgical technique in the regenerative treatment of isolated interdental intrabony defects. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 36(2)(2003), 157–163. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19207892/

Graziani, F., Gennai, S., Cei, S., Cairo, F., Baggiani, A., Miccoli, M., … Tonetti, M. (2012). Clinical performance of access flap surgery in the treatment of the intrabony defect. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 39(2), 145–156. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22117895/

Graziani, F., Gennai, S., Cei, S., Ducci, F., Discepoli, N., Carmignani, A., & Tonetti, M. (2014). Does enamel matrix derivative application provide additional clinical benefits in residual periodontal pockets associated with suprabony defects? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 41(4), 377–386. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jcpe.12218

Retzepi, M., Tonetti, M., & Donos, N. (2007). Comparison of gingival blood flow during healing of simplified papilla preservation and modified Widman flap surgery: A clinical trial using laser Doppler flowmetry. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 34(10), 903–911. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17850609/

Trombelli, L., Farina, R., & Franceschetti, G. (2007). Uso di un solo lembo in chirurgia ricostruttiva. Dental Cadmos, 8, 19–26. http://dentalcadmos.ecm33.it/cont/default-approfondimento/approfondimento-68all1.pdf