PERIO FOR THOUGHT - March 16, 2021

“Tissue Integrated Prosthesis”, was the title of the first textbook in Implant Dentistry, published by P.I. Branemark in the late 70’s. Although for the decades that followed, it was osseointegration that dominated Implant Dentistry, today, 50 years later we can see Branemarks textbook’s title more current than ever! Tissue remains the issue, not only for function and aesthetics, but mainly for long-term, sustainable health. The critical tissue is no longer the bone, but mainly the few millimetres of the supracrestal peri-implant soft tissue, where human-tissues, bacteria and mechanical components interact to determine sustainable health or disease! This is our modern battleground in Implant dentistry and many factors can influence the outcome of this battle. Could the soft tissue dimensions be one of them? let’s take a deeper look in the current evidence..!

Peri-implantitis is one of the major long-term threats for the success of implant therapy and a classical case where prevention pays high dividend. Identifying and mitigating the relevant risks is therefore a major effort at present and research is targeting many local and systemic directions. As part of these efforts, the dimensions of the peri-implant soft tissues have been attracting a lot of attention lately, looking for a possible link to peri-implantitis. Often approached as “thickness” or “height”, emerging studies are pointing towards risk identification in the dimensions of the peri-implant soft tissue. But how far have we come in this direction?

To name it is to know it

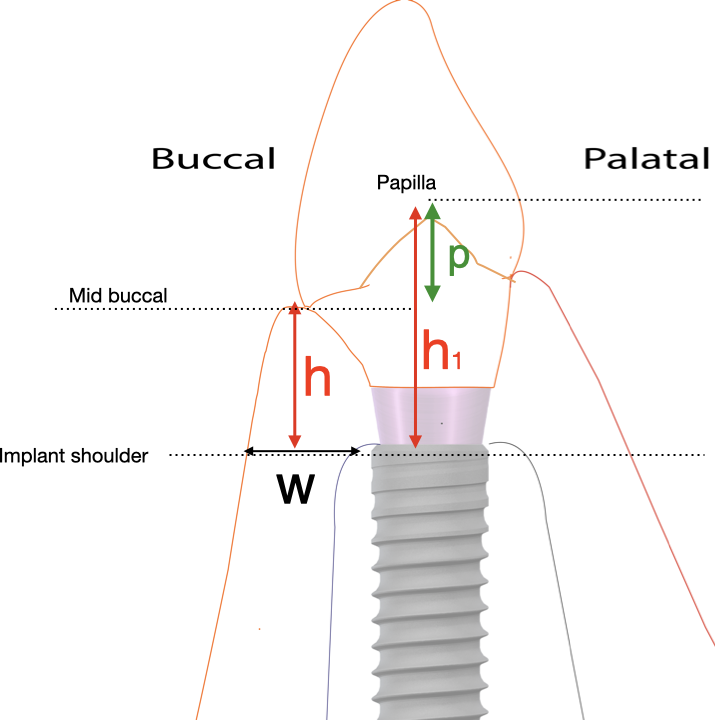

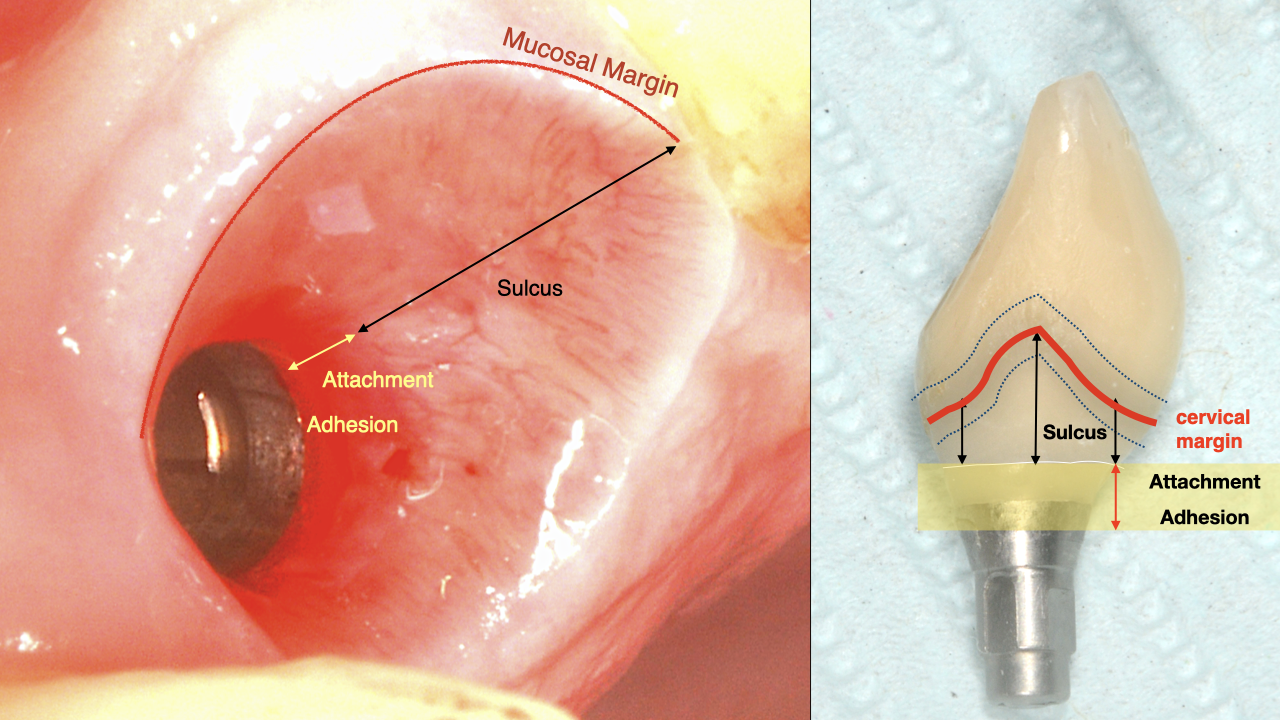

To start with, we need to define what we are looking for. In the oral mucosa of the edentoulous alveolar ridge, it is easy to define soft tissue “thickness” or “height” in the rather simple anatomic arrangement. Once an implant with a prosthesis comes in place however, the soft tissue acquire a specific orientation and defining structures, which require precision in our terminology. Any investigation related to soft-tissue dimensions should then be defined in relation to the tissue orientation and structure. Concepts such as “tissue thickness” become rather vague in the case of the peri-implant tissues, unless precisely defined. Therefore, for the purpose of setting a baseline please allow me to define the critical dimensions we are discussing as in the figure: (Figure 1,2).

Having clarified what we are looking for in the tissue dimensions, let’s also define the outcome we are investigating, which is plaque induced peri implant tissue inflammation such as Mucositis and Peri-implantitis, with emphasis in the terms “plaque-induced”..!

Peri-implant tissue dimensions and peri-implantitis

So now we come to the million-dollar question. Could it be that the height or width of the peri-implant tissues can be linked to the risk for peri-implantitis?

And here lies the first confusing part, as most recent research on soft tissue dimensions has focused on the Marginal Bone Loss, in particular bone loss which occurs in the first 3-12 months after placement. Such bone loss in the short term can be many things, but is very unlikely to be due to Peri-implantitis, which is a plaque-induced chronic inflammation and requires significant time to be established and be manifested with bone loss. Furthermore, Peri-implantitis is not radiographically diagnosed. The latest consensus workshop on Periodontal and Peri-implant diseases (1) has provided some very clear case definitions for the diagnosis of peri-implantitis in daily practice, as well as teaching and research, all of which include clinical documentation of the presence of inflammation with outcomes such as bleeding on probing and probing depth. Consequently, studies which relate the soft tissue dimension (mainly before implant is placed) with radiographic marginal bone loss without investigating or documenting the presence of inflammation, are not studies that speak of Peri-implantitis. To make a long story short, in my mind, any marginal bone loss that occurs within the first 12 months after implant placement is very unlikely to be because of Peri-implantitis. What is this bone loss, does it really happen, why it happens and should we be really bothered about it, all these might be a very good discussion for ...another time!

For now back to our original question...!

Peri-implant tissue height and inflammation

So what do we know about the size of the soft tissues and risk for actual plaque induced inflammation? Are there any research studies out there with the parametres we are looking for?

Well, here things become rather tight, as there is a lot of discussion but very little true results to base it on! I have struggled to find some proper studies that can help us answer these questions and to the best of my knowledge I have only found two: One clinical study (2) and one experimental mucositis (3).

Zhong, et al. (2020) concluded that the risk for peri-implantitis increases by 1.5 times for every mm of increase in the vertical soft tissue thickness. At first sight, this conclusion is as clear as it gets! But looking a bit closer, we realise the devil, as always, lies in the detail. The study conducted one measurement of soft tissues and that was at the palatal site of the flap at the time of implant installation. This would correspond to the vertical height of the pre-surgical oral mucosa at the edentulous ridge site, but whether and how this measurement correlates to the circumferential peri-implant soft tissue height after implant placement, healing and remodeling is completed, - even more after the implant is restored - is up to debate. Then a correlation is presented between the mucosal height at the surgery with probing depths and bleeding on probing from a single examination more than two years after surgery. Unfortunately, there are no baseline measurements on the condition of the soft tissues, Soft Tissue Height, Bleeding on Probing or Probing Depths at the time of the prosthesis connection. Think that implants with initially higher soft tissues would also have initially deeper sulcus depths and initially deeper probing readings. There might be an obvious confounding factor there, when we only base our diagnosis on the absolute value of probing depth at 2 years, when we do not know what it was at baseline. There is an obvious correlation between initial peri-implant tissue height and probing depth, which cannot alone indicate the initiation of Peri-implantitis, unless is followed up prospectively.

As the study includes tissue and bone level implants (without mentioning transmucosal or submerged healing protocols), conventional and immediate implantation, loading times from 3 to 6 months, it becomes very difficult to account for the potential impact of such differences in the post-surgical and early tissue healing and remodelling. This fact makes it more difficult to extrapolate from the pre-surgical thickness measurement to the long-term clinical outcomes related to peri-implant inflammation.

Nevertheless, despite some limitations, the study points to a direction. In my mind, it is not the pre-surgery tissue height that matters, but risks start with the peri-implant tissues when the implant is placed and restored. We can’t change the mucosal thickness of the alveolar ridge, but we can influence to a great extend the morphology of the peri-implant soft tissues by designing the Implant Supracrestal Complex.

The second study I would like to discuss is a carefully conducted experimental Mucositis by Chen et al. In this case we do not have Peri-implantitis as an outcome, but we do have a very detailed study of the initiation and establishment of peri-implant tissue inflammation. This time the study included the actual peri-implant tissues and studied the vertical height of the soft tissue from the implant shoulder to the mucosal margin. This space was defined as Mucosal Tunnel in the study and in the case of the tissue level implants included, this would correspond the full or partial length of the peri-implant sulcus. The design was simple and powerful. Two groups of implants were organised, these with a shallow tunnel (1mm or less) and these with a deep one (3mm or more). Health of peri-implant tissue was ensured with oral hygiene and prophylaxis at baseline and then all patients abstained from oral hygiene. Unsurprisingly, after 3 weeks all implants developed Mucositis. What turned out to be different however was that the inflammatory burden as expressed by the concentration of interleukin was higher in the group with deeper sulcus, while the clinical resolution of Mucositis was more difficult in this group and was achieved through removal of the crown and cleaning. At this point I would note that the study used Tissue Level implants, adding one more parameter, as the implant-abutment junction in such implants can be a difficult to reach plaque retension point, if it is located deep in the sulcus.

This study offers two important conclusions in my understanding. First, as it was shown at baseline, in the presence of proper maintenance care (professional maintenance and patient performed oral hygiene), the depth of the sulcus did not limit the ability to achieve healthy peri-implant tissues, neither it reduces the risk for peri-implantitis if oral hygiene is not practiced. Furthermore, during the plaque accumulation phase, inflammatory response appears to develop in the same manner in both groups. Second, upon established inflammation, treatment for implants with deep peri-implant sulcus might present with more challenges than those with a shallow one.

Peri-implant tissue width and inflammation

Peri-implant tissue width or thickness is a parameter frequently discussed, in particular with regards to aesthetic outcomes, but there is really not much in terms of evidence for risk of peri-implantitis. Many colleagues would recommend augmentation of peri-implant tissues as a prevention measure to reduce among others the risk of peri-implantitis. Leaving aside any aesthetic considerations, the expectation that augmenting the volume of the peri-implant tissues will prevent plaque induced inflammation sounds to me unfounded in biology. We never considered augmenting thin periodontal tissues to prevent periodontitis, did we? Some might say that peri-implant tissue, as a repair tissue is a compromised tissue in many ways. True. The compromise however is structural not dimensional. It is a tissue that is less vascularised, less cellular, more fibrous, less structured and less mechanically attached to the local anatomic landmarks. How would the increase in volume compensate for such structural compromise? If nothing else, could it be that we might cause even more structural compromise when we attempt to surgically thicken peri-implamnt tissues with autografts or xenografts, by introducing more trauma, scar tissue or biomaterials?

Questions that are left to be debated... But for now, I do not see any evidence of thick peri-implant tissue being any less likely to suffer from plaque induced inflammation than the thin one. Even more, I do not see any evidence justifying “preventive” augmentation of the peri-implant tissue for the sake of peri-implantitis.

Conclusively...

The peri-implant soft tissue is our current battlefield, where long term health can be won or jeopardised. It is almost self-evident that the peri-implant soft tissue morphology and structure is crucial to winning this battle, but to do this we need to define the outcomes more precisely and to study the soft tissues in closer relation to the “bigger picture”. To build on the very good analogy of the “mucosal tunnel”, studying the tunnel is only meaningful when we know the train which is going to pass through it. Consequently, we will need to evolve the discussion by defining concepts and terms which will collectively describe the tunnel, as well as the train. We are evolving fast from initially wide terms such as “thickness” and “height”, to better define the microanatomy of the tissues, with an adhesion zone, attachment zone and sulcus, in close proximity with design features of the mechanical components in one Implant Supracrestal Complex (4). We are only at the start of this paradigm and I believe new exciting research is on the way!

The vertical height of the peri-implant tissues is critical for the establishment of a healthy peri-implant seal. The practice of securing at least a total of 3-4 mm for the undisturbed establishment of the peri-implant soft tissues remains the current standard. Increased vertical height will result in deeper peri-implant sulcus. If you have to accept this for aesthetic purposes, make sure that the prosthesis part corresponding to the sulcus opening is completely accessible to oral hygiene. At the end of the day, it’s a plaque induced disease we are trying to prevent. If we establish the anatomic conditions for good plaque control, we will all have less to worry about!

References

1. Berglundh, T, et al. (2018). Peri-implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol, 45 Suppl 20:S286-S291. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12957Canullo

2. Zhang, et al., (2020). Influence of vertical soft tissue thickness on occurrence of Peri-implantitis in patients with periodontitis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res, 22(3):1–9. doi:10.1111/cid.12896

3. Chan, D, et al. (2019). The depth of the implant mucosal tunnel modifies the development and resolution of experimental peri-implant Mucositis: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol, 46:248-255. doi:10.1111/jcpe.130662.