Changing the patient - July 01, 2020

What are the principles of motivational interviewing? How can they be applied effectively in clinical practice? How can the motivational interviewing help clinicians in the treatment of periodontal disease?

The article will provide you with technical-scientific information about the principles of the motivational interviewing. This communication method has proven to be effective in the management of various risk factors related to periodontitis and this article summarizes its benefits by providing practical examples and results from the latest scientific literature.

Management of risk factors in periodontal patients: which strategy to use?

The progression of periodontitis is linked to etiological causes and risk factors, as identified through clinical and epidemiologic research. Controlling individual risk factors, alongside oral hygiene instructions, is fundamental for the improvement of periodontal treatment results during active treatment and the maintenance of periodontal health during supportive therapy (Ramseier et al., 2020). Many of these risk factors are associated with the lifestyle and the behaviour of the patient, thus may be controlled through psychological counselling interventions (Newton & Asimakopoulou, 2015).

In the medical setting, these counselling interventions are well adopted and represented by expert recommendations and instructions. However, this method seems to be inadequate in the management of behaviour-related periodontal risk factors. Therefore, the adoption of evidence-based psychological interventions should be encouraged during periodontal therapy as a fundamental part of the treatment. An example of an evidence-based and structured counselling approach is motivational interviewing (MI) which was developed by Miller and Rollnick (Rollnick & Miller, 1995), also recommended for use in the field of periodontology (Sanz & Meyle, 2010).

The principles of motivational interviewing

“Motivational interviewing is a patient-centred, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence” (Rollnick & Miller, 1995).

The motivational interviewing is a method of collaborative communication, and its main purpose is to develop a strong alliance between the counsellor and patient using empathy, evocation and autonomy to raise intrinsic motivation within the patient for behaviour change.

To do so, there are two main groups of strategies, discussed in further text: i. 4 main communications skills to implement a guiding style of communication and ii. six major principles that characterised Motivational Interview specifically.

The four communications skills are summarised by the acronym OARS: Open questions, Affirmations, Reflective listening and Summarizing.

Open questions, instead of closed ones, help clinicians to gain a deeper understanding of the patient’s lifestyles and values (Ramseier & Suvan, 2010). Affirmations demonstrate acknowledgement for the patient’s attempts and support the patient to develop their self-awareness of being able to change. (“You are a very determined person/It’s clear that it is important to you to be../You really tried to work on this new behaviour”). Reflective listening facilitates the listener to confirm whether he or she understood what the patient meant (“It sounds like...”) At the end it is important to summarise and demonstrate that the clinician has listened and understood what the patient said.

In addition to these communication techniques, six major principles outline the core of Motivational Interviewing.

i. Clinicians should express empathy using reflective listening and affirmations, focusing on the patient’s perspective.

ii. They should try to develop discrepancy between the patient behaviour and his/her values, exploring them through open questions.

iii. Supporting self-efficacy is important as, in fact, beliefs that people have about themselves are essential to the choices they make regarding behaviour change.

iv. The use of evocative open-ended questions such as “Do you remember a time when things were going well for you? What has changed? From a scale from 0 to 10, how important do you find your teeth? How confident are you to change this behaviour?” can enhance the patient’s confidence in achieving their goal and elicit change talk. The so-called change talk is the patient’s statement about change. Through these statements, patients express the desire to change or reveal that they have the skill to change and/or realise the benefits of behaviour change (Catley et al., 2014). An example of a change talk is given in Table 1.

v. In addition to this, clinicians need to educate the patient by raising their awareness about a specific topic. However, to do so, they must get an understanding of what the patient already knows and ask permission before providing information related to the patient’s interest. Accordingly, the clinician should avoid advising unless desired by the patient.

vi. The last principle lies in negotiating a plan for change. The patient needs to have in mind what exactly he/she will do, how he/she can get started, when and where the new habit will occur (Koerber, 2014). In this case, the clinician should avoid drawing up the perfect ideal plan. On the contrary, the patient, with the support of the clinician, develops his own plan for change.

In the end, the clinician should summarise the goal of the MI intervention.

|

Speaker |

Statements |

Behaviour code |

|

Clinician |

Tell me a little about what you like about smoking. |

Open-ended question |

|

Patient |

Well, I like smoking because it makes me feel relaxed. I’m very busy at work at the moment, and I have to look after my wife and my two children. |

Sustain talk |

|

Clinician |

So, without cigarettes, it would be hard for you to relax from work and busy family life. |

Complex reflection - affirmations |

|

Patient |

Yes, exactly, sometimes it’s the only escape from all my busy life. |

|

|

Clinician |

Can you now maybe think about some benefits in quitting? |

Open-ended questions |

|

Patient |

My breath will not smell as bad, and my wife will be happier. I like to play football with my friends. Maybe my performance would be better too. |

Change talk |

|

Clinician |

Well, it seems that there are some important benefits for you! |

Affirmation and reflective listening |

|

Patient |

Yes, exactly. I don’t want my wife to worry about me and my health. However, despite these benefits, I’m not able to quit. |

Change talk with reasons/ express ambivalence about smoking cessation |

|

Clinician |

On a scale from 0 to 10, how confident are you that you can change? |

Support change: evocative question (Importance ruler) |

|

Patient |

4 |

Talk |

|

Clinician |

Why 4, and not 3? |

Evocative question |

|

Patient |

Because last year I managed to quit for 2 months. |

|

|

Clinician |

Good! Tell me a bit more about those two months. How did you feel? (…) |

Evocative question |

The scientific evidence behind MI

A systematic review of randomised control clinical trials showed that MI has positive and long-term outcomes when applied for smoking cessation, nutrition counselling for the obese and promotion of physical activity (Lundahl et al., 2013).

In particular, a Cochrane systematic review validated MI interventions for smoking cessation (Lai et al., 2010): MI leads to more cessation attempts, increases readiness to cease smoking and increments quit rate. Moreover, MI is considered highly efficient compared to other methods.

For the first time, a recently published trial investigated the relationship between the language of dental counsellors and their patients in periodontal therapy in the context of MI (Kitzmann et al., 2019). The statements made by the counsellor who was using the MI principles were statistically significantly correlated with patients’ language in favour of change (change talk) with an Odds Ratio of 1,31 (Kitzmann et al., 2019). This implies MI statements evoked a language for change from the patients quickly.

A systematic review by Carra et al. evaluated the impact of psychological interventions aiming at promoting behavioural changes to improve oral hygiene in periodontal patients (Carra et al., 2020). The literature suggests that combined psychological interventions based on individually-tailored oral health educational programs, social cognition models and MI may lead to an improvement of oral hygiene, measured by decreased plaque scores and gingival bleeding (Carra et al., 2020; Jönsson et al., 2009).

Alongside oral hygiene behaviour, other risk factors can be addressed during periodontal treatment. MI might be applied for further risk factor control purposes, including tobacco discontinuance, diabetes control, weight reduction or diet change.

A systematic review aiming to identify the most recent guidelines for risk factors control interventions underlined that smoking cessation and diabetes control interventions in the dental setting might improve periodontal health (Ramseier et al., 2020) and thus need to be integrated in periodontal care.

Motivational interviewing as a part of periodontal treatment

Brief interventions could be successful in supporting patients’ behaviour change while taking up only 5-15 minutes of the dental appointment. Each brief intervention may accomplish one simple step toward behaviour change, with a cumulative effect over time (Ramseier & Suvan, 2010).

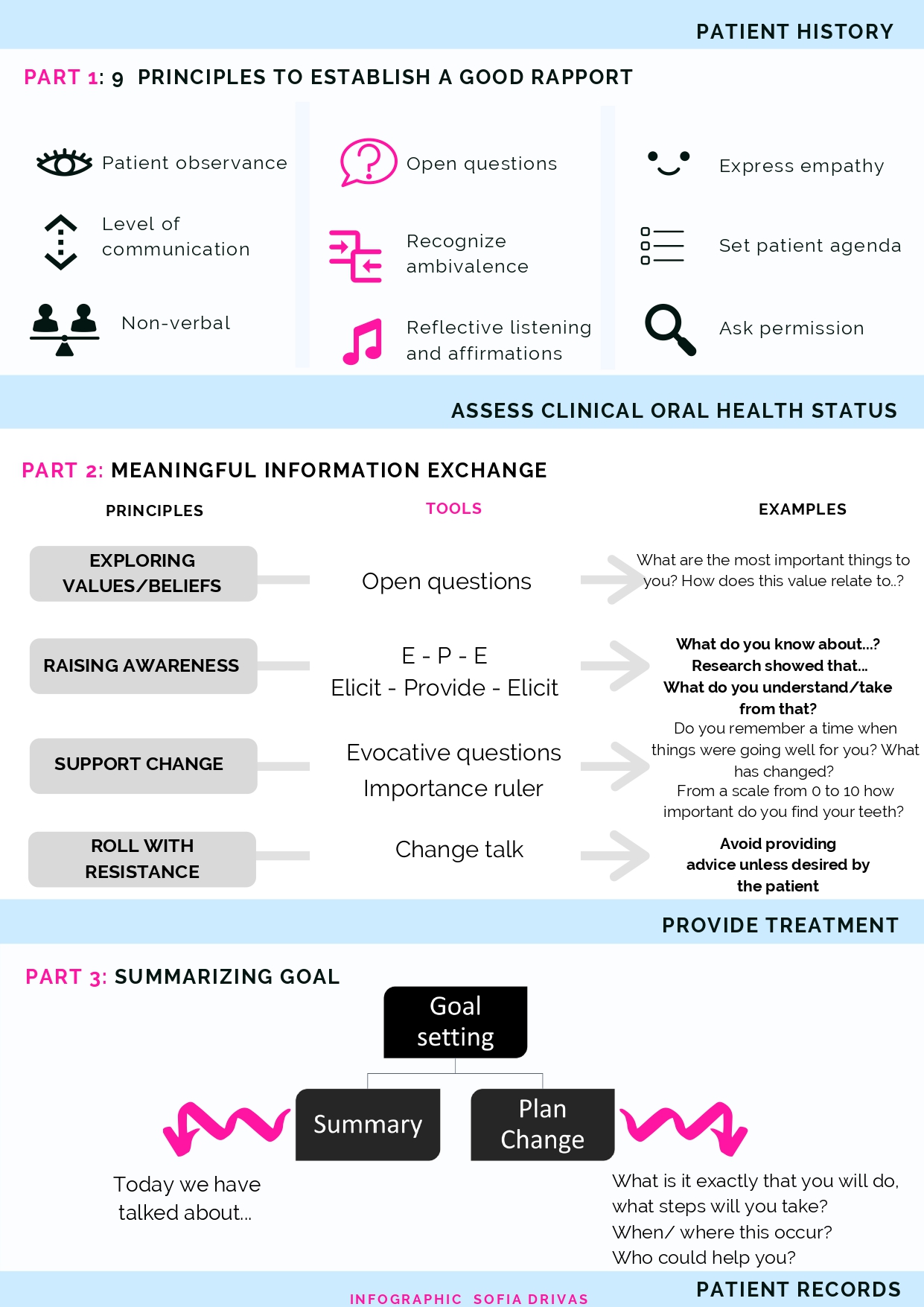

The major principles of MI can be easily used throughout a dental appointment.

The opening part of the appointment is to engage with the patient using an open question that seeks the patient’s prime reason for attending the visit or explore his/her main concerns. Keeping eye contact at the same level of the patient is essential. Before assessing clinical oral health status, the clinician asks permission to go on with the oral assessment. This has proven to be indispensable to honour the patient’s autonomy.

The second portion of communication between the patient and the clinician takes place after the check-up. The information exchange starts with what the patient already knows and then the clinician provides information, and explores what sense the patient makes of information provided (Suvan et al., 2014). During this time the clinician can verify the confidence the patient has or the importance that patient gives toward a behaviour change (i.e. using interdental toothbrushes daily or modifying his/her diet) and how they feel about it.

Then after having provided the treatment, the last part of the appointment is dedicated to summarising what was said during the visit and, in particular, about behaviour change discussions. It provides the clinician to review the goals and to plan, together with the patient, a detailed strategy to achieve this goal.

Below you will find a handout that can be printed and used as a reminder for MI principles in the dental setting. It can be used during a dental hygiene appointment where BAND 1, 2 and 3 correspond to the three-part of communication described in this section (Table 2).

MI is a collaborative, person-centred form of guiding to elicit and strengthen. The clinician should consider himself the patient’s mentor, recognising their ambivalence and raising their awareness about a specific health-related issue. MI interventions are proven to be effective in health behaviour change in various fields, thus gaining increasing interest in the field of periodontology as well. Evidence-based recommendations for methods to manage behaviour-related risk factors of periodontitis are needed (Kitzmann et al., 2019). However, consensus guidelines on standardised protocols that would guide on the type of psychological interventions and the number of sessions needed are still missing (Carra et al., 2020).

Tips and tricks |

|

Literature and suggested reads:

Carra, M. C., Detzen, L., Kitzmann, J., Woelber, J. P., Ramseier, C. A., & Bouchard, P. (2020). Promoting behavioural changes to improve oral hygiene in patients with periodontal diseases: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, n/a(n/a). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31912530/

Catley, D., Goggin, K., & Lynam, I. (2014). Motivational Interviewing (MI) and its Basic Tools. In Health Behavior Change in the Dental Practice (pp. 59–92). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118786802.ch4

Jönsson, B., Öhrn, K., Oscarson, N., & Lindberg, P. (2009). The effectiveness of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on oral hygiene behaviour in patients with periodontal disease: A blinded randomised-controlled clinical trial (one-year follow-up). Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 36(12), 1025–1034. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01453.x

Kitzmann, J., Ratka-Krueger, P., Vach, K., & Woelber, J. P. (2019). The impact of motivational interviewing on communication of patients undergoing periodontal therapy. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 46(7), 740–750. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jcpe.13132

Koerber, A. (2014). Brief Interventions in Promoting Health Behavior Change. In Health Behavior Change in the Dental Practice (pp. 93–112). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118786802.ch5

Lai, D. T., Cahill, K., Qin, Y., & Tang, J.-L. (2010). Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD006936. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub2/full

Lundahl, B., Moleni, T., Burke, B. L., Butters, R., Tollefson, D., Butler, C., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling, 93(2), 157–168. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0738399113002887

Newton, J. T., & Asimakopoulou, K. (2015). Managing oral hygiene as a risk factor for periodontal disease: A systematic review of psychological approaches to behaviour change for improved plaque control in periodontal management. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 42(S16), S36–S46. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jcpe.12356

Ramseier, C. A., & Suvan, J. E. (2010). Health Behavior Change in the Dental Practice (1. ed). Blackwell Pub. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781118786802

Ramseier, C. A., Woelber, J. P., Kitzmann, J., Detzen, L., Carra, M. C., & Bouchard, P. (2020). Impact of risk factor control interventions for smoking cessation and promotion of healthy lifestyles in patients with periodontitis: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, n/a(n/a). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jcpe.13240

Rollnick, S., & Miller, W. R. (1995). What is Motivational Interviewing? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246580001643X

Sanz, M., & Meyle, J. (2010). Scope, competences, learning outcomes and methods of periodontal education within the undergraduate dental curriculum: A Consensus report of the 1st European workshop on periodontal education – position paper 2 and consensus view 2. European Journal of Dental Education, 14(s1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0579.2010.00621.x

Suvan, J., Fundak, A., & Gobat, N. (2014). Implementation of Health Behavior Change Principles in Dental Practice. In Health Behavior Change in the Dental Practice (pp. 113–144). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786802.ch6